Agencies

AgenciesIt was a bright, cold day, somewhere in Central Asia, and the clocks were striking thirteen. The year was 1984. The Michael Jackson album, Thriller, had just been released to critical acclaim. Steve Jobs, sans turtleneck, had unveiled the first Apple Macintosh at the Flint Centre in Cupertino. Across the pond, Margaret Thatcher had survived an assassination attempt by Irish secessionists at a hotel in Brighton.

In the City of Angels, P.T. Usha was forsaken by providence, missing out on a bronze medal at the Olympics by one hundredth of a second. There was no ticker tape parade. On the Fourth of July - America's national holiday - Ringo Starr gave a rendition of The Beatles' hit track, "Back in the USSR" to a sold-out crowd in Washington D.C. But back in the Soviet Union, stranger things were afoot.

The ill-fated Reactor 4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was just commissioned. Safety checks were bypassed. At Star City, a high-security closed military township on the outskirts of Moscow, two Indian Air Force (IAF) officers awaited their fate. Ravish Malhotra and Rakesh Sharma were more than just compatriots who fate had brought together in terra incognita. They were both of Punjabi extraction, and adherents of the strict military code that wingmen are bound to. However, at the thirteenth hour, only one of them would be handed a return ticket to the cosmos.

On April 2, 1984, the Soyuz T-11 took off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome at precisely 13:08 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Hidden away in the backwoods of the USSR, the launch facility was situated in modern-day Kazakhstan - far away from the prying eyes of the Americans, with whom the Soviets were walking lockstep in a Space Race. Rakesh Sharma, who was aboard the spaceship, watched the earth recede to a mere speck on the horizon. As the Soyuz T-11 hurtled into outer space, the din of the engines was gradually replaced by the silence of the steppe.

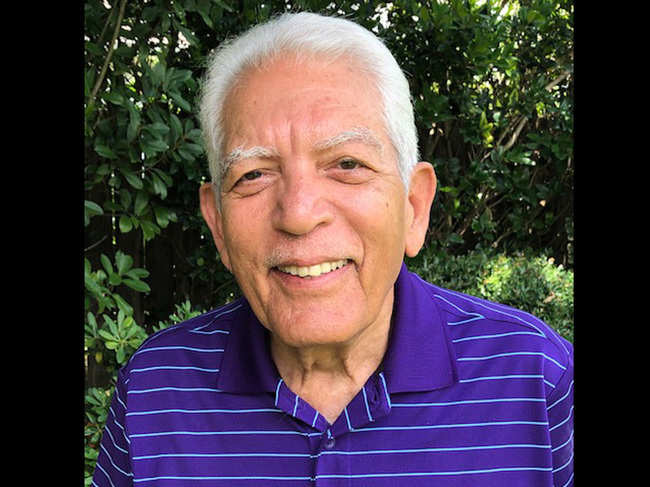

Ravish Malhotra watched his comrade take to the skies from the control centre at the Baikonur Cosmodrome. "Right from the beginning, it was known that only one of the two of us would go up into space with the Russians. The other would be a standby," he says in a video interview from Houston. Malhotra, 75, who is visiting his son in the U.S., says that the spartan lifestyle he led in Moscow all those years back has held him in good stead.

"I still do basic exercises every day for about 45 minutes. Apart from this, I walk around 35 km every week," he says. Dressed in a purple t-shirt, Malhotra cuts a dapper figure, not far removed from the iconic image of him in a spacesuit, taken during the training programme. "The exposure to space technology and cosmonaut training has been a cherished experience," he says. But the road to Houston, via Moscow, has been long and winding.

Silent Night, Mottled Dawn

Ravish Malhotra was born on Christmas day, 1943 - the year of the Bengal famine. The British were fighting a war on multiple fronts whilst struggling to maintain a stranglehold on their colonial empire. The Malhotras, who were living in Lahore, were largely insulated from the political turmoil around them. But things changed after India's tryst with destiny. At the midnight hour on August 15, 1947, while the world slept, India awoke to freedom. The scepter of Partition passed over the map of the subcontinent. Millions were displaced. Thousands lost their lives.

"I was only five years old when my family shifted from Lahore to Delhi. I was too young and don't remember any details, except that we stayed with my father's elder brother in Delhi after migrating from Lahore," Malhotra says. His parents eventually settled down in Calcutta, with Ravish and his three siblings shifting base yet again. The Malhotra brothers attended St. Thomas School, Calcutta, one of the oldest institutions in the country. Upon graduation, a young Ravish gave the entrance exam for the coveted National Defence Academy (NDA). He was admitted.

"Three of my cousins were in the Navy, and I had made up my mind to join them," he says. However, fate intervened, and instead of his first preference, he was drafted into the IAF. Malhotra became a commissioned officer in 1963 and was inducted to the "Vampire Squadron", a group of pilots who flew the eponymous British fighter jet. He was posted at the Air Force base in Barrackpore, a Calcutta suburb not too far from his childhood home. "It was a stroke of destiny that I joined the Air Force and not the Navy. I am glad that it happened as otherwise, I wouldn't have been a part of this great adventure that was about to unfold," Malhotra says with a chuckle.

Waiting In The Wings

As a rookie pilot, Malhotra flew the Vampire jet but soon outgrew the WWII-era aircraft. As he explains, "the more service you put in, you are upgraded to better aircraft". Malhotra was subsequently shifted to air bases in forward posts like Ambala and Pathankot. He also got to fly more sophisticated aircraft like the Dassault Mystère, the American F - 111 Bomber, and also the indigenous HAL HF-24 Marut.

Eventually, Malhotra graduated to the cockpit of the Soviet-made Sukhoi Su-22, the then marquee fighter jet of the IAF. In the meantime, trouble was brewing on the western front, necessitating Malhotra's return to the land of his birth.

Battle Scars

In 1971, Pakistan launched preemptive aerial strikes on 11 air bases in India, prompting New Delhi's entry in the war in East Pakistan. The IAF was deployed, and air raids were performed to aid the advance of ground troops in the two-front war. Malhotra was stationed at a base in North India, and was a part of the fighter squadron tasked with launching cross-border strikes.

"I flew the Sukhoi - 22, a ground attack aircraft, and performed 17 sorties across the border in support of our Army on the western front. Many a time, I came back with bullet holes in my aircraft from enemy anti-aircraft guns. By God's grace, I was very lucky unlike some of my colleagues whom we tragically lost," he says. Some members of his squadron were taken as prisoners of war (POWs), and a few were eventually repatriated to India.

"Wing Commander Dilip Parulkar and I were a part of the same squadron. His aircraft was shot down over Pakistan and he was taken captive. We feared the worst. He escaped from jail but was captured again. Eventually, he was returned to India. We are in touch," Malhotra says. Parulkar's capture and eventual homecoming is the subject of the crowdfunded film, The Great Indian Escape. Others were not quite so lucky. Some went missing, and were not heard from. They were presumed dead.

Space Beckons

The war had ended with a decisive Indian victory. East Pakistan was liberated. Bangladesh was born. Life returned to normalcy, and restive calm prevailed. After the war, Malhotra was selected to undergo the Test Pilot's course at the USAF Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California. "Being a test pilot was a plus point for being selected for astronaut training," he says. He was then shortlisted to take part in the Indo-Soviet Space Mission. "I considered it to be a great honour. Can you imagine being one of the two people selected for the mission, out of our population of over a billion Indians?" he asks wistfully.

The criteria for selection included excellent fitness of mind and body. Being a pilot was a prerequisite for being considered. As Malhotra elaborates, "Experience as a test point was a further plus point as it implied a better understanding of avionic systems." From a large batch of candidates, eventually four were shortlisted for extensive tests at the Institute of Aerospace Medicine in Bangalore and sent to Moscow for further medical evaluation. At the end of the final medical tests in Moscow, Rakesh Sharma and Ravish Malhotra were selected.

Up In The Air

What followed was rigorous training for the better part of two years at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center at Star City. The medium of instruction was Russian. "It took us about three months to become proficient in the language. This was a compulsory requirement since all dials and equipment in the spacecraft had inscriptions in Russian. Also, the Soviet cosmonauts and team members did not speak English," Malhotra reminisces. The language lessons were followed by classroom sessions on the theory of space flight.

Cadets at Star City had to acclimatize themselves with the various systems on the Soyuz T-11, including life support systems. They also had to practice emergency procedures that could crop up when flying the spacecraft. Their daily routine included theory classes in the morning. This was followed by practical training on the spacecraft simulator, as well as on a mockup of the Space Station, in the afternoon. The crew of cosmonauts hit the gym in the evening to improve their fitness levels.

Apart from work on the simulators, they were also given training in extraterrestrial conditions. "Micro-gravity conditions were simulated on earth by taking the cosmonauts in an IL-76 aircraft, which was fully padded on the inside. The aircraft did 'over the top' maneuvers, which is similar to an outside loop. This creates near zero gravity conditions for about 45 to 50 seconds," Malhotra says. During this period cosmonauts are trained to maneuver in zero gravity conditions akin to that in space. Several such maneuvers were done on each test flight, and a number of such flights were undertaken.

Agencies

AgenciesBack To School

"We had to familiarize with some of the specialized equipment such as the space suits used during launch and descent. We were also trained in sea survival since the Soyuz capsule is recovered over the sea," Malhotra reveals. Although the families of cosmonauts were permitted to join them during the training period in Moscow, they had to partake of their meals at the mess hall. Diet intake was controlled, and physical exercise was monitored.

This, Malhotra says, was done to ensure peak fitness levels and minimize the chance of falling ill during the space flight. The strict fitness regimen was followed by all cosmonauts, although they were allowed the liberty of indulging on occasion. "The food was basically Russian preparations since we had to eat at the special mess facility. As far as drinks were concerned, I did enjoy the odd beer during weekends. The Russians, of course, preferred vodka," Malhotra says.

The nature of their training meant that they were mostly restricted to interacting with Russian handlers throughout the work week. On weekends, they would fraternize with officers and diplomats from the Indian Embassy, particularly the defence attachés posted in Moscow. "It was but natural for us to adapt to the Russian culture. In the defence services, we move around a lot and hence coping with the new environment was not difficult for our families," Malhotra says. Despite the competitive nature of the programme, the training brought about greater kinship among the participants. Some friendships would last a lifetime.

Ricky And Mallu

In the end, there were two. Out of the four Indians who were shortlisted for the Indo-Soviet Space Mission, only Ravish Malhotra and Rakesh Sharma made it to the end of the training period. Sharma and Malhotra were acquaintances before traveling to the Soviet Union. "We were colleagues at the Aircraft and Systems Testing Establishment in Bangalore," Malhotra says. However, it was during their time in the USSR that the two became thick friends. They were allies whose fates were intertwined with each other.

Rakesh became Ricky, and Ravish, Mallu. "Everyone called him Ricky. Malhotras in the air force are called Mallus," Malhotra says. They were tasked with carrying out specific tests in zero gravity, one of which was to study the effects of yoga in space. Malhotra does not practice yoga anymore. But there were other thoughts running through their minds during the arduous training programme at Star City. The Soviets were infamous for their lack of transparency. External inspection of their facilities was not allowed. But Malhotra was unconcerned.

"At no point did I feel worried about the safety of the Russian equipment. They had very robust systems, and were very advanced in the field of metallurgy. In fact, Russian spacecraft operate at 760 mm of pressure, which is same as on earth. When compared to this, NASA's spacecraft operate at 480 mm of pure oxygen," Malhotra explains. On April 2, 1984, the Soyuz T-11 took off from Baikonur. There were no technical glitches. Rakesh Sharma was launched into orbit with two other cosmonauts - Yuri Malyshev and Gennadi Strekalov.

"I was disappointed, but you accept it, and move on with the mission," says Malhotra. He adds that the final decision on who would go into space was taken by the Ministry of Defence in New Delhi. More than three decades later, Malhotra insists there has never been any sort of rivalry between the two. "Both Rakesh and myself are very good friends and have mutual respect and admiration for each other. Although he lives in Conoor, we always meet up whenever he is in Bangalore, which is where I live," he says.

The Voyage Home

Sharma was in space for seven days and 21 hours. Four parachutes, deployed 15 minutes before touchdown, slowed the spacecraft's rate of descent. One second before landing, two sets of engines on the bottom of the vehicle fired, slowing the vehicle considerably, softening the landing. The three cosmonauts were whisked away from the landing pod. Ricky and Mallu were reunited. In India, they received a hero's welcome.

"The then Prime Minister, Mrs. Indira Gandhi took personal interest in the programme. In Delhi, we were felicitated by the President, the Prime Minister and other functionaries. Subsequently, both of us, along with our families, were honoured by Governors of every state in the country," Malhotra says. He was awarded the Kirti Chakra in 1984. After initial hullabaloo, life went back normal. Malhotra returned to a combat role in the Air Force. He was appointed the Commanding Officer of the Hindon Air Force Station near Delhi.

Malhotra took premature retirement in 1995, and after the specified cooling off period, ventured into business. "I set up a state of the art Aerospace Manufacturing Facility from scratch for a friend of mine in Bangalore. It is called Dynamatic Aerospace, and is a part of Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. I stopped working when I turned 75, which was about a year ago," Malhotra says. Dynamatic Technologies, which builds precision instruments, has an order book which includes the likes of Airbus, Boeing, and Bell helicopters. Dynamatic Technologies is listed on the National Stock Exchange.

The Final Frontier

Malhotra, who is a sprightly 75, is still enthusiastic about advancements in space technology. When quizzed about the Indian government's plan to send another man to space, he exuded confidence in the proposed mission, but jokingly excluded himself from the running. "Well, this time it will be on an Indian spacecraft, which will be launched by an Indian rocket. I am sure ISRO is confident of sending our own astronauts into space. It will be a great leap forward for India," he opined.

At the height of the Cold War, both sides made advances to developing countries to widen their sphere of influence. The then-Indian government - whilst harbouring socialist leanings - remained noncommittal. The joint space mission, of which Malhotra and Sharma were a part of, was described by Indira Gandhi as being the fruits of a longstanding friendship between the two countries. A New York Times editorial dated April 4, 1984, hailed the achievement as "peaceful use of outer space", even taking a dig at the Reagan administration in Washington for militarizing space through the development of anti-satellite weapons.

Malhotra, who is a product of that age, is staunchly apolitical, but sees great potential in aerospace technology as a tool in modern diplomacy. "Space can be used as an instrument of foreign policy. An excellent example of this is the launch of the South Asia Satellite, which will aid communication and meteorology studies in neighbouring countries," he says. However, Malhotra remains skeptical of commercial space flights on account of the prohibitive cost and the challenges that untrained civilians will have to contend with.

"As I understand, currently no guidelines have been laid down (for civilian astronauts). A daily exercise routine will be necessary to be healthy for undertaking any space flight. Fitness norms of commercial space travelers will, I presume, not be as stringent as with military astronauts," he says.

Elon Musk-owned SpaceX recently announced that it would be ferrying space travelers as early as 2023. Yusaku Maezwa, the Japanese fashion tycoon, will have the honour of being the first civilian on the moon. He bought a berth on the spacecraft for an undisclosed sum. But Malhotra, who has made peace with the events of 1984, is more enthused by Gaganyaan - India's first crewed orbital spacecraft.

Astronauts have generally been selected from the talent pool of the IAF, and Malhotra expects the current crop of fighter pilots to emulate his feats when the mission is given the go ahead. "'Touching the Sky with Glory' is the motto for the IAF. When India sends up its own astronauts, in indigenously built spacecraft, using an indigenous launch vehicle, even the sky will not be the limit anymore. It will be a proud moment for all of us," he adds.

Few Indians have served in warzones. Fewer still, have defied gravity. Malhotra, who is no stranger to self-sacrifice, insists the key to success lies in perseverance and humility. "I suppose one has to stay grounded. After the Indo-Soviet Space Mission got over, I went back to my old life in the Air Force. I often chat with my grandchildren about my experiences during that period," he says.

Get Unlimited Access to The Economic Times

Get Unlimited Access to The Economic Times