Chainmail-like polymer could be the future of body armor

Researchers supported by grants and instrumentation provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation have created the first 2D polymer material that mechanically interlocks, much like chainmail, and used an advanced imaging technique to show its microscopic details. The material combines exceptional strength and flexibility and could be developed into high-performance and lightweight body armor that moves fluidly with the body as it protects it.

The nanoscale material was developed by researchers at Northwestern University and the electron microscopy was conducted at Cornell University. The results are published in a paper in Science.

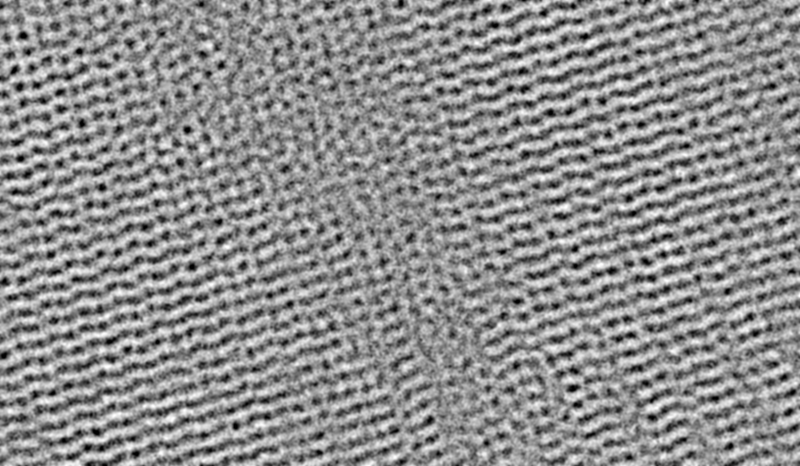

Credit: David Muller, Schuyler Shi and Desheng Ma/Cornell University

Groundbreaking in more ways than one, the paper describes a highly efficient and scalable polymerization process that could potentially yield high volumes of this material at mass scale. In addition to being the first 2D mechanically interlocked polymer, it also contains 100 trillion mechanical bonds per 1 square centimeter — the highest density of mechanical bonds ever achieved in a material.

"We made a completely new polymer structure," says William Dichtel, a researcher at Northwestern University and one of the study's authors. "It's similar to chainmail in that it cannot easily rip because each of the mechanical bonds has a bit of freedom to slide around. If you pull it, it can dissipate the applied force in multiple directions."

The creation process involves coaxing polymers to form mechanical bonds, a feat that has challenged researchers for years. The research team created a novel process to make these bonds happen: arranging ordered crystalline structures of polymer molecules and then causing the crystals to react with another molecule to create bonds inside the crystal's molecules. The resulting crystals comprise layers and layers of 2D interlocked polymer sheets.

The polymer's crystallinity and interlocking structure were confirmed at Cornell University, where an advanced electron microscopy method was used to atomically image a crystalline material for the first time.

"The results were remarkable — sharp and high-contrast — clearly revealing the structure," says Schuyler Zixiao Shi, a doctoral student at Cornell University who conducted the imaging.

Dichtel credits the paper's first author and doctoral candidate Madison Bardot for creating this innovative method for forming the mechanically interlocked polymer. "It was a high-risk, high-reward idea where we had to question our assumptions about what types of reactions are possible in molecular crystals," says Dichtel.

Collaborators at Duke University tried adding the chainmail polymer material to Ultem, a strong and protective material in the same family as Kevlar. The researchers developed a composite material of 97.5% Ultem fiber and just 2.5% chainmail polymer that significantly boosted Ultem's toughness.

"We have a lot more analysis to do, but we can tell that it improves the strength of these composite materials," Dichtel said. "Almost every property we have measured has been exceptional in some way."

Distribution channels: Science

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release